Miss a day, miss a lot. Subscribe to The Defender's Top News of the Day. It's free.

By Neil Gordon and Walter M. Shaub, Jr.

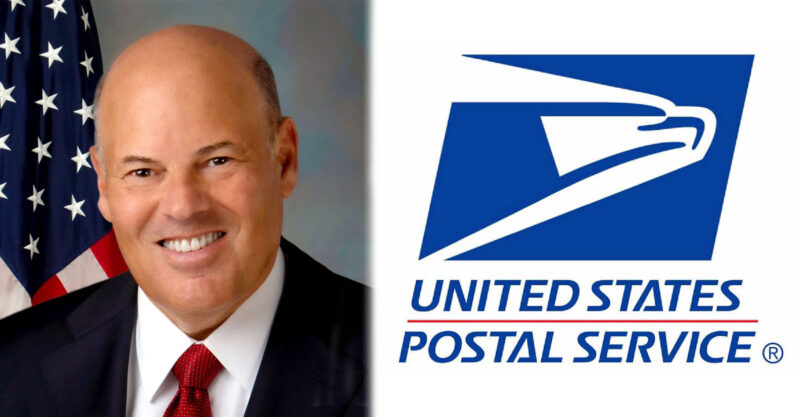

As part of a government program established this year, the United States Postal Service is distributing free COVID-19 test kits to the public — an initiative that could add to the personal wealth of Postmaster General Louis DeJoy.

DeJoy has reported owning stock in one of the companies supplying the tests, and his financial disclosures show no evidence of him having fully divested that stock. In failing to do so while participating in the COVID-19 free test project, DeJoy may have violated a federal conflict-of-interest law.

Before becoming postmaster general in June 2020, DeJoy spent over 30 years as an entrepreneur and business executive. He reportedly has a net worth of $110 million.

His most recent annual financial disclosure report, covering the calendar year 2020, lists a staggering number and variety of assets and income sources. It also shows that, between June 15, 2020, and Dec. 31, 2020, he reported a whopping 861 transactions.

In January 2022, President Joe Biden announced that the government would purchase 500 million rapid COVID-19 tests, with four tests kits to be mailed to all American households upon request.

In March, the White House announced that the public could request a second set of four test kits.

It is one of the largest disaster relief efforts in the Postal Service’s nearly 250-year history, involving hundreds of processing centers, thousands of post offices, and hundreds of thousands of workers.

DeJoy, who has logistics and supply-chain expertise as the longtime owner of a trucking company, was reportedly “intensely involved” in the logistics of the project and has been among its most vocal advocates.

One of the primary suppliers of the tests is medical products company Abbott Laboratories, which stands to earn a hefty profit from the test giveaway. Abbott has already sold the federal government millions of its popular BinaxNOW COVID-19 tests.

As an Abbott Laboratories stockholder, DeJoy could reap a benefit, too. According to his annual disclosure, as of Dec. 31, 2020, DeJoy owned between $150,002 and $350,000 of stock in Abbott Laboratories.

A subsequent transaction disclosure shows that in August 2021, he sold between $50,001 and $100,000 of his Abbott stock. A review of all of his publicly available financial disclosure reports — the most recent report was filed in early March — shows no evidence that DeJoy sold all of the rest of his shares.

DeJoy not only owned Abbott Laboratories stock, but he also appears to have traded the stock after the White House announced on January 7 that the COVID-19 test kits the administration had purchased would be “sent out through the mail.”

On January 11, two days before the federal government formally announced that it had awarded Abbott Laboratories a $306 million contract for the test kits, DeJoy engaged in two transactions involving Abbott.

In a disclosure he filed on February 2, DeJoy described one of the transactions, which he valued at $1,001-$15,000, as an “opened written call option position.” He described the second transaction, which he valued at $15,001-$50,000, as a “closed written call option position.”

A financial disclosure guide on the website of the Office of Government Ethics directs filers like DeJoy to describe a stock option as a “written call option” when the filer has given someone else the right to buy stock from the filer at a specified price.

On March 24, the federal government awarded a contract modification to Abbott Laboratories worth over $1 billion for test kits.

Federal ethics law concerns

A federal conflict-of-interest law bars officials like the postmaster general from participating personally and substantially in certain government matters affecting their own financial interests.

The law doesn’t cover every government undertaking, but it does cover programs that, like the free COVID-19 test project, are focused on the interests of individual companies or a specific industry.

Under the conflict-of-interest law, it doesn’t matter if another government official, or even another federal agency, negotiated the deal with the test manufacturers.

It also doesn’t matter if the official ultimately never makes a profit from the conflict of interest — the law is intended to avoid even the risk that personal finances will influence the performance of official duties.

DeJoy’s stock ownership can trigger the ban on participating in any aspect of the project, whether that’s assisting with logistics or public relations.

For this reason, some of DeJoy’s public comments about the project may have stepped over the line.

“The 650,000 women and men of the United States Postal Service are ready to deliver and proud to play a critical role in supporting the health needs of the American public,” he announced in January, assuring the public that the Postal Service was “well prepared to accept and deliver test kits.”

A few weeks later, DeJoy again drove home the significance of the project and boldly declared, “It is a major point of pride throughout our organization to have met our own performance expectations and those of the public.”

These comments constitute personal and substantial participation in the project. As the head of the Postal Service, DeJoy’s comments serve as public relations messaging for the free COVID-19 test project. This involvement raises concerns about whether he is complying with the conflict-of-interest law.

The risk of a potential conflict of interest here is a product of DeJoy keeping a wide range of investments and continuing to engage in trades.

Top executive branch officials normally steer clear of conflicts by selling off holdings in companies that have interests affected by their agencies. Not DeJoy. Earlier this year, he filed a disclosure listing 26 trades in December alone, including shares in drug companies like Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Pfizer.

The month before, he had reported 16 trades. This trading activity — and even owning stocks in individual companies — is risky business for the head of an agency that’s directly involved in interstate commerce. It puts DeJoy in danger of crossing the line separating what’s legal from what’s not.

When reached for comment, a spokesperson for the Office of Government Ethics told Project On Government Oversight (POGO) that the agency does not discuss specific individuals.

A Postal Service spokesperson seemed to confirm to POGO that DeJoy worked on “the logistics of delivering” the test kits. But the spokesperson emphasized that the conflict-of-interest law is triggered only when an employee participates “personally and substantially” in a project and that the Postal Service didn’t choose the test kit suppliers.

This response is only partially correct. To understand why it’s necessary to know how the conflict-of-interest law works. It’s true that the law is triggered only by personal and substantial participation in a project.

But the Office of Government Ethics has consistently told ethics officials that nearly any participation by an agency head is deemed “substantial.” The office’s regulations also explain that supervising the work of subordinates on a project amounts to “personal” participation.

And, in this case, DeJoy participated even more directly than as a supervisor when he publicly promoted the project.

The Postal Service spokesperson also made another common mistake in pointing out that the agency didn’t select the test kit companies. As we have already noted, this is irrelevant.

A government employee’s participation in any part of a particular matter triggers the conflict-of-interest law, even when another agency is carrying out parts of the effort, like choosing contractors or suppliers for a project.

Precedent for investigation

If it turns out that DeJoy’s conduct did run afoul of the conflict-of-interest law, it wouldn’t be the first time for a postmaster general. In the 1990s, the Justice Department sued Postmaster General Marvin Runyon for civil monetary penalties.

The government alleged that Runyon had participated in negotiations with Coca-Cola to put soft drink vending machines in post offices while holding about $350,000 in the company’s stock. Runyon settled the case by paying the government $27,550.

The public shouldn’t have to second-guess whether DeJoy is more concerned with his stock portfolio than ensuring Americans get their mail, packages, prescriptions, and COVID-19 tests on time.

Congress, the inspector general of the United States Postal Service, the Justice Department’s Public Integrity Section, and other federal officials should investigate whether DeJoy’s involvement in the COVID-19 test distribution violated federal conflict-of-interest law, which comes with civil and criminal penalties.

Originally published in Project On Government Oversight.

Neil Gordon is an investigator for the Project On Government Oversight.

Walter Shaub is a senior ethics fellow at Project On Government Oversight.