By Richard Schiffman

Plastic is everywhere we turn — in bags and water bottles, in the synthetic fibers in clothing and carpets, in cellphones and tires, in wind turbines and solar panels.

We wrap our fruits and vegetables in it, and we use it to make astroturf and computer chip components. Plastic in one form or another shows up in virtually every device that our modern lives depend on.

The ubiquitous material is increasingly making its way into the soil, into the sea, into our drinking water, into the air we breathe and ultimately into the very cells of our bodies. And the problem is only going to get worse: A 2022 report projects that plastic production will triple by 2060.

One of the problems is what to do with the plastic once we’ve used it. In recent years, only about 5% or 6% of the plastics we use in the U.S. end up getting recycled.

Judith Enck became acutely aware of the issue as a regional administrator for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under President Barack Obama. After leaving government service, she went on to found the activist environmental group Beyond Plastics, where she is currently president.

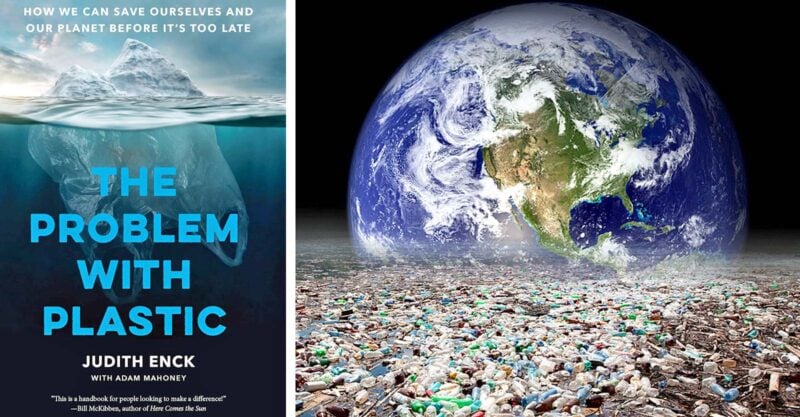

Despite the deepening crisis, there is still room for hope, Enck maintains in “The Problem With Plastic: How We Can Save Ourselves and Our Planet Before It’s Too Late,” written with environmental journalist Adam Mahoney. (Beyond Plastics is also listed as a co-author.)

They focus on two main solutions: We need to produce far less plastic and become better at reusing what we do make.

Much of the book chronicles how the threat of plastic pollution has escalated since the 1950s, when consumer goods and containers made of plastic flooded the marketplace.

More than 16,000 different chemicals are used in the production of plastics, including the notorious “forever chemicals,” or per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), commonly found in consumer and industrial products.

While most of our plastic waste goes to landfills, every minute roughly two garbage-truckloads of plastic trash wash down rivers or are otherwise dumped into the sea.

Many of us have seen pictures of accumulated plastic trash floating like rafts on the ocean’s surface — usually in coastal areas. Discarded plastic fishing nets entangle dolphins and other marine mammals. Seabirds eat plastic nodules, mistaking them for food.

Every year, plastic pollution kills “up to 1 million seabirds, 100,000 sea mammals and marine turtles, and untold numbers of fish,” the authors write.

The toll is staggering. One study found that fish that ingest plastic particles swim more sluggishly, grow more slowly, and show less appetite. Albatross chicks that dine on plastic have died from dehydration or starvation. Researchers have recently identified a disease called plasticosis that scars the digestive tracts of seabirds.

The images of coastal rafts of plastic bags and bottles, styrofoam containers and candy wrappers are shocking enough, but it’s what we do not see, the authors write, that poses the greatest threat.

Large pieces of floating plastic eventually break down into smaller pieces called microplastics, which in turn get broken down into even tinier pieces called nanoplastics (smaller than one micrometer).

These microscopic particles have been found in everything from whales to krill and plankton at the bottom of the marine food chain. Blue whales filtering seawater for food take in an estimated 10 million tiny pieces of plastic a day.

Enck and Mahoney cite the growing body of scientific evidence that microplastics are now ubiquitous in our food supply. Some leach into our food and beverages from plastic water bottles and other kinds of packaging.

They also show up in apples and carrots and countless other agricultural products, introduced into the soil from a variety of sources, including artificial mulch, irrigation water and sewage.

Meanwhile, according to 2018 data from the EPA, 27 million tons of plastic trash end up in U.S. landfills every year, and 5.6 million tons are incinerated annually. Burning plastic releases a mix of greenhouse gases that in 2020 had an environmental impact equivalent to 15 million tons of CO2, in addition to emitting mercury, lead and sulfur dioxide.

Plastic pollution is suspected of being a factor in the rise of several noncommunicable diseases, especially those related to the endocrine system, like diabetes, reproductive cancers and cardiovascular disease.

Microplastics that are small enough to enter the bloodstream are showing up in human lungs, livers, placentas and kidneys, as well as in breast milk and semen. The authors cite research that estimated the disease burden from plastic pollution adds $250 billion annually in healthcare costs in the U.S.

While we are all affected, it is the poor who are the most severely impacted.

“By design, low-income people and communities of color bear the burden of plastic,” the authors write. “The destructive web of plastics gathers in their neighborhoods, rivers, air and bodies.”

The book is dedicated to people living in the shadow of plastic facilities in the “cancer alleys” of Louisiana, Texas and Appalachia, where fossil fuel production is centered.

The authors argue that the big oil companies see plastic manufacturing as a way to continue profiting from fossil fuels even as the world transitions to cleaner energy sources.

So what is to be done about this global calamity? The usual answer involves recycling, a solution pushed by the big fossil fuel companies, which have spent millions of dollars on advertising campaigns that the authors claim are designed to shift the blame for plastic pollution from producers onto consumers.

Yet recycling is “largely a myth,” the authors persuasively argue.

“Plastic recycling wasn’t designed to fix the problem,” they write, “it was designed to help us feel better about it. The industry sold us a dream.”

Most plastic products cannot be successfully recycled due to their highly complex chemistries. And according to a 2017 study, of all the plastics ever produced, only 9% have ever been recycled. The attorney general of California has sued Exxon Mobil for what he claims are its false recycling claims.

That doesn’t mean we should stop recycling altogether. Some items, like plastic bottles, can be recycled and should be, Enck and Mahoney emphasize. And plastic bag bans and bottle bills work: States that have bottle bills reduce beverage container litter by as much as 84%.

But far too much plastic is being produced. We need to wean ourselves off single-use plastics, find ways to reuse what we already have, use refillable water bottles, buy fruits and vegetables that are sold without plastic packaging and wear clothing made from natural rather than synthetic fibers.

The authors do focus primarily on plastic pollution in the U.S., with only brief mentions of how the rest of the world is coping with the problem, and little about the so-far unsuccessful effort to enact a global plastics treaty. Such efforts are particularly important for developing nations, where the plastic waste crisis is often the most acute.

“The Problem With Plastic” is both an activist call to arms and a thoroughly researched survey of the latest science on plastic pollution, offering a compelling and impassioned argument about how we can do better — not just as individuals but as a society.

What the authors do best is convince us that there is no cause to feel hopeless. The same human creativity that invented plastics can find a way to prevent them from further harming the planet and the creatures that we share it with.

In the end, Enck and Mahoney caution readers not to go down the rabbit hole of trying to eliminate all plastics from our lives. That’s simply not possible. Guilt-tripping ourselves won’t work.

What will work, they say, is supporting policies that sharply reduce the production of plastic and ensure that what does get produced gets reused, when possible, and safely disposed of.

“We’ve made it clear that individual choices are a part of combating the crisis, but it is not a substitute for getting into the political arena to drive change,” the authors write.

“Systemic change is crucial: Supporting legislation, collective advocacy, and holding corporations accountable for reducing plastic production are essential for lasting progress.”

Originally published by Undark.

Richard Schiffman is an environmental reporter and author based in New York City.