Miss a day, miss a lot. Subscribe to The Defender's Top News of the Day. It's free.

CNN last week published an article stating, in the headline, that in about half of U.S. counties, less than 10% of children ages 5 to 11 are fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

For those who understand mainstream media’s tactics for motivating people to comply with the COVID-19 vaccination campaign, the CNN article follows a predictable script:

- Report on the concerningly low rate of vaccination.

- Remind readers of the threat of COVID.

- Find a source of data that supports vaccine effectiveness.

- Underplay the risk of vaccine adverse events.

As I explain below, this media strategy was extremely effective nearly one year ago, in the spring of 2021, when COVID vaccines were readily available in the U.S. but vaccine uptake lagged medical authorities’ expectations.

Before we take a look back at the 2021 story, let’s examine this latest CNN article and how it targets parents who are reluctant to vaccinate their young children, especially children ages 5 to 11.

Low vaccination rates in children and exaggerated risk of COVID

CNN quoted Dr. Yvonne Maldonado, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases, who said:

“This has been a constant concern for all of us. It’s very disturbing to see that families just haven’t embraced [vaccination].”

Maldonado is a Stanford professor of pediatrics whose research program received funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to investigate the poor immunogenicity of the oral polio vaccine in Mexico.

She also is a non-voting member of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

Maldonado is one of several liaison representatives on the ACIP who represent organizations with broad responsibility for administration of vaccines to various segments of the population, operation of immunization programs and vaccine development.

So why aren’t families embracing vaccination?

According to Maldonado, “This basically is a risk perception issue, that families don’t feel that their children are at risk for getting severe disease.”

This “risk perception” is quite reasonable. CNN cited CDC data that demonstrate 345 total COVID deaths in the 5 to 11 age group since the beginning of the pandemic, more than two years ago.

As the CDC reports, kids ages 5 to 11 comprise 8.7% of the U.S. population, or approximately 29 million individuals — so this is a mortality risk of 0.0006% per year in this age group.

Despite this exceedingly low risk of death from COVID, Maldonado warns, ”We can’t risk-stratify children. We can’t predict which children are going to be at risk for hospitalizations.”

Her statement stands in opposition to the CDC.

According to the CDC, children with comorbidities such as “medical complexity, with genetic, neurologic, metabolic conditions, or with congenital heart disease” and “similar to adults, children with obesity, diabetes, asthma or chronic lung disease, sickle cell disease, or immunosuppression might also be at increased risk for severe illness from COVID-19.”

Sick kids get sick — that’s what the CDC says. They are the ones who are going to be at risk for hospitalization.

Exaggerated vaccine effectiveness

CNN cited a study, published March 30 in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), that claims a 68% vaccine effectiveness in preventing hospitalization in children ages 5 to 11.

This is a surprising finding given, as The Defender reported last month, that observational data from New York involving several hundred thousand children of this age demonstrate Pfizer’s vaccine plunged to only 48% effectiveness in preventing hospitalization within a few weeks.

Moreover, according to the New York data, the rate of hospitalization in the unvaccinated children of that age was six per million during the last week of the seven-week period of observation.

The absolute risk of hospitalization due to COVID-19 in this age group is very low.

How did the authors of the NEJM study obtain such a large protective benefit of the vaccine, contrary to the New York observational data involving a thousand-fold more children?

The study had several shortcomings, including:

- The median time since vaccination (in the vaccinated children) was 34 days and at least 14 days before onset of illness. This is the period of maximum vaccine effectiveness.

- The study failed to account for natural immunity (children in the study were not screened for previous COVID infection). CDC’s own study confirms those with prior infection had 2 to 6 times less risk of hospitalization than those vaccinated.

- Six of the NEJM study’s authors are CDC employees.

The NEJM study was of “case–control, test-negative design.” This means the control group was not unvaccinated. Instead, they were children hospitalized for reasons other than COVID.

This type of study requires that the controls are matched patients undergoing the same tests for the same reasons at the same healthcare facility and who test negative.

However, according to the study:

“Each matched control patient was selected from among the patients who were hospitalized within the same institution as the case patient, were in the same age category as the case patient, and were hospitalized within 4 weeks before or after the date of admission for the case patient.”

The control patients were indeed of the same age and hospitalized at the same facility around the time of COVID patients — but they were not hospitalized for the same symptoms.

In other words, the authors calculated the vaccination rates in two groups of hospitalized children, one where they were hospitalized for COVID and the second, where they were hospitalized for other reasons (the test-negative control group).

Because the vaccination rate was higher in the non-COVID hospitalized children, the authors claimed a protective effect of the vaccine against COVID hospitalizations.

It is clear that this approach to estimating vaccine effectiveness is fraught with uncertainty and confounding factors.

Which group had a greater exposure to the disease? (We don’t know.) Which group was sicker to begin with? (The COVID-19 children were: 82% had comorbidities versus 73% in the control group.)

This approach also opens the door to a simple means to manipulate the vaccine’s calculated effectiveness.

If the authors preferentially included vaccinated children in the control group and unvaccinated children in the COVID group, the vaccine effectiveness would be exaggerated.

If they did the opposite, the effectiveness would be not only marginal, it would be negative.

With no further details about how the control group was selected, we are left to speculate.

How can this kind of comparison lead to any meaningful assessment of the vaccine’s effectiveness in preventing hospitalization from COVID-19?

“It doesn’t,” Dr. Meryl Nass told The Defender.

Nass, an internist and member of the Children’s Health Defense scientific advisory committee, said there’s something else that is puzzling about how the authors recruited their participants.

According to the study, 537 children were chosen from 31 different pediatric hospitals over a period of nine weeks.

This means that on average, only a single pair of matched children (same age, admitted to the same hospital, at the same time) were chosen from each facility per week of the study — this during a time of an apparent surge of admissions from Omicron.

“This is a remarkably low recruitment rate, especially given that these were pediatric hospitals that were, apparently, seeing high levels of hospitalizations from Omicron,” Nass said.

“Why were patients enrolled in the study so slowly?” Nass asked. “Were they being cherry-picked from a large number based on their vaccination status? Or weren’t there enough admissions to begin with?”

The study also was designed to calculate vaccine efficacy in preventing “critical” cases of COVID — in other words, those leading to life-supporting interventions or death.

However, there weren’t enough critical cases in the 5-11 age group for a proper analysis to be conducted.

Nevertheless, unvaccinated children were underrepresented in the critical COVID subgroup compared to all children hospitalized with COVID (90% vs 93%). Vaccination did not protect against critical disease.

Finally, of the children hospitalized with COVID, more than four of five had an underlying comorbidity.

Again — sick kids get sick.

Downplaying the risk of vaccines

The CNN article acknowledged vaccines come with risk:

“The most common vaccine side effects in children and adults include aches and fever. But there has been a slight increase in the risk of myocarditis, which is inflammation of the heart muscle, and pericarditis, inflammation around the heart, which has happened occasionally in males 16 to 39 who were vaccinated.”

According to the CDC, the background incidence of myocarditis is approximately 0 to 2 per million per week.

In a week-long period following the second dose of COVID vaccine to 18- to 24-year- old males, the CDC acknowledges (slide 3) approximately 69 cases of myocarditis per million.

By a “slight increase” CNN is referring to 34 times or greater risk in this large age group. This is the risk that the CDC acknowledges. Other studies indicate that the risk is higher still.

A recent study from Hong Kong suggested the incidence of myo/pericarditis after two doses of Pfizer’s Comirnaty vaccine was 37 in 100,000 (370 per million).

This incidence matches nearly exactly with findings from a study that used the Vaccine Safety DataLink system, which showed 37.7 12- to 17-year-olds per 100,000 suffered myo/pericarditis after their second vaccine dose.

These rates are almost six times higher than the 69-per-million rate reported by the CDC.

In a preprint study from Kaiser Permanente, the incidence of myocarditis in 18- to 24-year-old males post-vaccination was even higher — at 537 per million, or 7.7 times higher than the statistics reported by the CDC.

Maldonado told CNN:

“We know that myocarditis in [the 16- to 39-year-old] group is mild and that it’s not the kind of myocarditis that we tend to see from other pathogens, other viruses or bacteria, or even from Covid disease itself. But that has been an issue that parents have really focused on.”

She’s right — it’s not the kind of myocarditis we see from pathogens or COVID disease.

The Defender in February reported on coroner’s reports following the death of two previously healthy teenage boys days after their second vaccination. Histopathologic findings demonstrated something unexpected: stress cardiomyopathy.

The magnitude of the risk of COVID vaccines in children is still unknown.

Dr. Eric Rubin, NEJM editor-in-chief and member of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s vaccine advisory panel, during an FDA hearing, acknowledged the pediatric trial did not offer any information concerning risk.

“We are never going to learn how safe this vaccine is until we start giving it,” Rubin said. “That’s just the way it is.”

We’ve seen this before

As mentioned previously, the CNN article is using a predictable and highly effective strategy to cajole the public to vaccinate, in this case, young children.

Ten months ago a similar and widely cited article ran on The Washington Post’s digital media platform.

The Post warned readers not to get too comfortable with the falling case and hospitalization rates the country was enjoying early in the summer of 2021.

Things were getting better, the article claimed, because people were getting vaccinated.

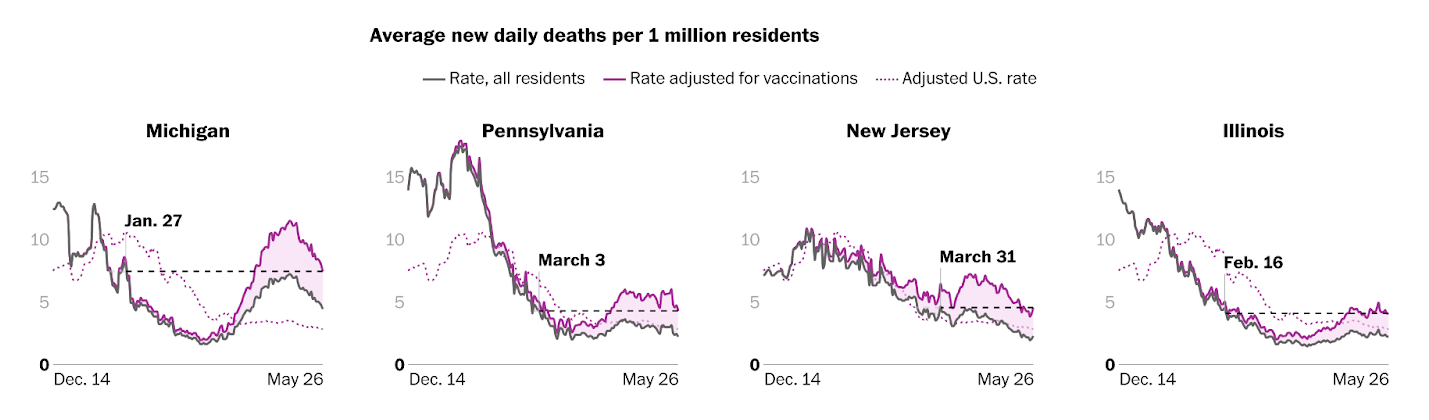

To demonstrate, the Post treated readers to a series of graphs comparing rates of infection among the vaccinated and unvaccinated in multiple states:

The divergence between the unvaccinated and vaccinated appeared in hospitalization rates in multiple states as well:

The Washington Post implied the same thing was apparently happening with regard to COVID deaths:

I was mystified when I read this article last year.

The vaccination status of those succumbing to COVID was not published. At the time, the CDC was willing to divulge only the TOTAL number of cases and deaths.

Where was the Post getting its data?

It turns out that the authors were not plotting the incidence of infections, hospitalizations and deaths of the vaccinated versus the unvaccinated.

Instead, they were plotting these rates in the entire population (data that was available) and creating a superimposed plot of what the rate would be in the unvaccinated if the vaccines were 85% effective.

The authors called this simulated plot “Rate adjusted for vaccinations” or in other graphs, “Adjusted for unvaccinated population.”

The authors assumed an 85% efficacy based on the findings of a small observational study with regard to case prevention. They took the liberty to use that same efficacy and apply it to hospitalizations and deaths in all states and the country as a whole.

The two plots in each graph diverged because more people were getting vaccinated, not because they were being protected.

In other words, it was a mathematical artifact of assuming that 85% of the vaccinated population could not be contributing to the cases, hospitalizations and deaths. As more of the population is vaccinated, the more the blame shifts to the unvaccinated.

Of course, the authors mentioned that that was what they were doing, in a “methodology” section at the end of the article.

However, the intent of the article was clear. Use the best strategy to compel the unvaccinated to comply: falsely blame the pandemic on them.

Stay tuned for more …

Now that the vaccine has been made available for children and there is even more hesitancy in the public, we should expect more of this kind of disingenuous and misleading messaging from corporate-funded platforms.